February 8th, 2023

It’s been about one month since I landed in France and there have already been three nationwide strikes. The fourth is happening this Saturday. The Macron government’s refusal to compromise on proposed pension reforms to raise the retirement age has resulted in frequent agitation and disruption.

As a student who attends Columbia University, I’m not unfamiliar with strikes; in fact, I started college the same year that there was a massive strike at Columbia. But now that I’m abroad, I can see a stark difference between American and French strike culture. Striking, called La Grève in France, is a cornerstone of culture here. In fact, it’s sometimes joked that striking is a national sport because of its historical significance.

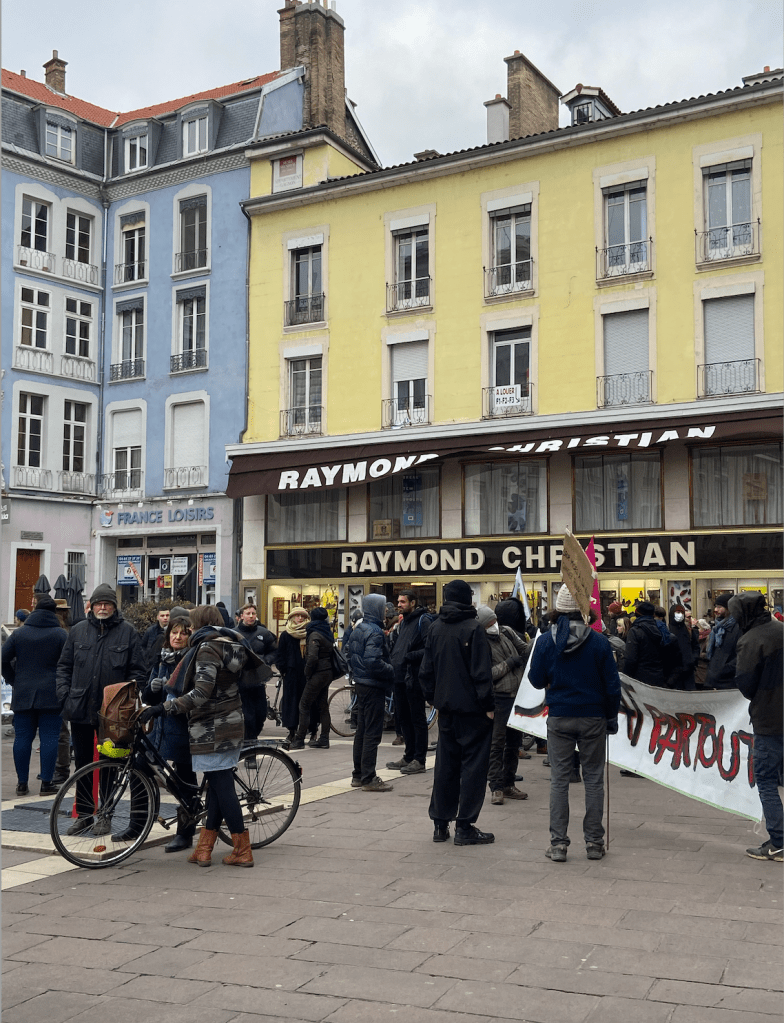

On January 19th, oblivious to this reality, I woke up and walked to get pain au chocolat and a coffee at 9am. I was greeted by a massive crowd that stretched for blocks and blocks. Numerous red flags with the letters “CGT” standing for the National Trade Union Center were waving. I heard loud chanting “On est où? On est là. ON EST LÀ”

“On est là” translates to “We are here,” and is a song often sung during social protests in France. When I heard it for the first time, it felt powerful. More specifically, it felt unifying, like a positive fighting force that permeated the air. Despite having one centimeter of personal space in that crowd, I felt a sense of peace.

My university classes were canceled or rescheduled on strike days. But professors did not express that much frustration. If they did, they referred to the inconveniences arising from public transport. But they never referenced the people, the strikers.

This was in sharp contrast to the strikes I’ve witnessed in the US. There is typically an “us”versus “them” mentality that arises. At Columbia, many of my STEM professors made comments referencing how “it was only the humanities that struck.” But in France, I felt an unspoken solidarity, which I’m assuming stems from the cultural importance of La Grève. Perhaps it is also related to the differing work-life balance between the countries. While the French are certainly not lazy, two hour lunch breaks are still common here. In the US, especially the city that never sleeps, there is the constant pressure to keep working because time is money. Some would even say that more Americans “live to work” instead of “work to live.”

In France, a balance is prioritized. Working is important, but it is not everything. France has one of the lowest retirement ages worldwide. And while this may be a problem for a government that needs to raise revenue, the country’s citizens are unwilling to forego that. To them, Macron’s reforms threaten their “work to live” rights.

Ultimately, while I may never truly understand the cultural significance of striking as an American in France, the recent strikes have caused me to reflect on my relationship with work. As an American, especially the daughter of immigrant parents, I have been taught to work all day. Productivity with tangible outputs is quintessential, and I’ve met many people with the mentality that a day’s success is measured by how much work is accomplished. But at the end of the day, I have to remind myself that as much as I want to work, I want to live too. Only by moving temporarily to France did I reassess my work-life balance and question whether I was content with it. So while I may have to walk thirty minutes or an hour to class the next time there’s a strike in France, I’m also grateful for the new perspective it’s provided me this past month.

Leave a comment